|

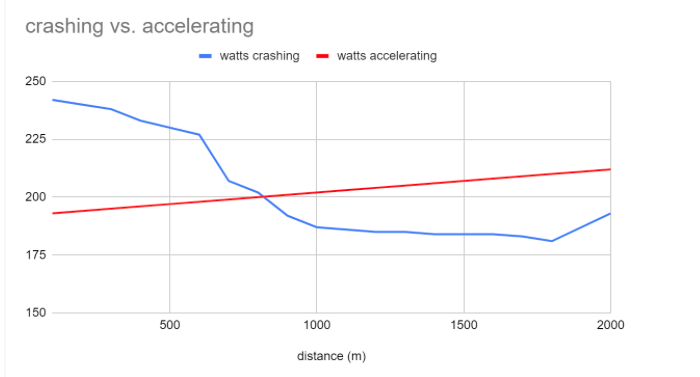

The quote “Don’t promise when you are happy, don’t reply when you are angry, and don’t decide when you are sad.” -Ziad K. Abdelnour is often thrown around to imply that intelligent and logical people often make unwise decisions based on emotion. I’ll add “Don’t grocery shop when you’re hungry and don’t make a race plan in the middle of a race” because no, of course I don’t need the ice cream and the donuts, and no, of course backing off to “save for the sprint” isn’t going to get me to my goal. Why should you have a race plan? What does having a race plan mean? And most commonly, what is the best race plan? Often I’ve gotten these questions just before or even during the warmup on 2k day. It’s a desperate rower’s hail-Mary, the hope that “there must be a key, some secret that if I can learn and execute will unlock the mystical erg test.” By then it’s too late to teach - too late to equip the rowers to answer those questions, so at that point I’ll give an example race plan, and if they’re lucky, they’ll have a relatively recent score to use as a starting point and we can craft a serviceable plan on the fly. But here in writing, when we have the luxuries of ample time and of logical thought, when we’re several stages removed from the heightened, anxious state that exists pre-erg test, here we can go into how and why to build an effective race plan. If there were such thing as a best race plan, then this wouldn’t be much of an article. Alas (or perhaps thankfully?) rowers will encounter different circumstances that require different race plans, and rather than try to prescribe a plan for every eventuality, we’ll lay out how to build your race plan based on your circumstances. “Why” to have a plan is summarized in the first paragraph - if you have no plan, then you’re going to fall back into emotional decision making. In the middle of an erg test or race piece, while the lizard-brain is elbowing in on your logical self with cries of “stop this madness!” is not the time to plan anything at all, let alone how hard you want to keep working for the next couple minutes. Circumstance 1 - “I don’t really know what I should aim for” This happens to novices, athletes coming off a long injury, or rowers who have come back to the sport after years off. If this is you, then, as soon as you can, get out of circumstance 1 - figure out what to aim for! How to do this? There are lots of “predictive workouts” (6x500, dirty dozen, 4x1k, etc), but in Philosophy of Science Norbert Wiener suggests that “The best material model of a cat is… the same cat” and I tend to agree. If you’re prepping for a 5k, do a 5k, if you’re prepping for a 2k, do a 2k. In fact, do several, because that’s the best way to simultaneously find an appropriate pacing and eliminate the foreboding that can accompany the erg test. Bear in mind that doing several 2ks isn’t “training” for a 2k, rather it’s a way of finding your correct pace. If you’re in this category, don’t get bogged down with an intricately detailed race plan, because at this point you’re just turning the coarse adjustment knob to get your pace somewhat in-focus. This is also where the “fly and die” has some value. While fly and die is not a good strategy for athletes who are trying to optimize and shave off 1 more second, for those who don’t know their pacing, it helps to “find your edge” if you’ve seen it from both sides. Circumstance 2 - “I have a goal, but how do I get there?” NOW, we can start building a race plan around something meaningful, and here are some questions to consider. What do you want your pacing to look like? Do you want to just hold steady for the bulk of the piece, or start 1-2 splits higher and work it down to -2/-3? Do you want to break it down by 500s/400s/300s and “castle” around your target average. Any of these are valid, but my usual prescription is to start a little slow, and accelerate throughout the piece. I like to think of it in terms of the percentage of the piece that is uncomfortable - see the charts below for a hypothetical comparison. The red line is a rower who paced to accelerate throughout the piece and the blue line is a rower who came out too fast (by about 7 splits) and then crashed. Both rowers wind up with the same time, but the blue rower is miserable starting at about 600, while the red rower probably gets uncomfortable around 800, but isn’t truly miserable until about 1200! What a savings! The red and blue examples are hypothetical, but are meant to trace more or less what a well paced, and poorly paced 2k could look like.

In general, the more you know about where you’re aiming, the more precise and tighter your pacing should be, for example: you’ve only done one 2k this season and it was 2 months ago? You could aim for +3/+0/-3/-(6+) over each 500, but if you’ve done several and you’ve got a pretty tight grouping, maybe you go for +1/+0/-1/-2. These are just examples, and I want to emphasize that the details of the plan aren’t as important as committing yourself to it- whatever it is. The Sprint - over the last ~15% or so you want to start committing a little harder, pushing deeper into the hole, so that by the last 20ish strokes, you’re going flat out. Use all the tools at your disposal here - pressure, rate, tech (efficiency). If your last 10 flat out strokes are just a couple splits below your average, or even if you crash in the last 5 and the split starts to climb, then you paced pretty well, but if your last 10 are wildly faster than your average, then you know you underestimated your capabilities, and you’ll want to try again and pace a little faster to home in on your hypothetical potential. Takeaway: build your race plan well in advance, Design it logically based off of previous (ideally recent) scores. If you don’t know where to aim, there’s nothing like the real thing to give you an idea. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

April 2023

Categories

|

|

Sammamish Rowing Association

5022 W. Lake Sammamish Pkwy NE Redmond, WA 98052 [email protected] 425-653-2583 |

Mailing Address:

Sammamish Rowing Association P.O. Box 3309 Redmond, WA 98073 |

|