Rowing and the Mental Side of the Sport

Here we hope to provide you with articles written by our coaches and community members to keep you involved in the sport while also educating you with our extensive collection of rowing knowledge! While you're at it, be sure to check out our opinions and articles on the mental side of the sport- a sometimes incredibly difficult terrain to navigate.

|

Rowing

Click the buttons below for quick access to our resources or scroll below to explore an array of different options

|

Mental

Train your mental skills like pro athletes do with the Champions Mind App. "The champions mind app is a great free tool to begin mindset training" - Coach Liza The Philosophy of Rowing from Rowing Faster, 2nd Edition

The Deep Love of Sculling- The Joy of Sculling by James C. Joy

|

Coaches Corner

Hear what you coaches have to say! Sammamish Rowing Association is bursting with incredible rowing knowledge shared collectively among our world class coaching staff. Below you can find more in depth information they want you to know!

Coach Liza: Finding Motivation

Finding Motivation to Train in a Time of Covid

One of the most common frustrations I have heard during this crisis from athletes of all ages, both from SRA and beyond is: “I don’t have the motivation to train without races and without my team. What do I do?” I want to highlight three words in this statement – motivation, races and team and discuss them further.

The first thing I want to address- there are races in your future! I know you don’t know exactly when, but you will race again. When that race day arrives, will be you be ready for it? And what does ready look like? Probably a little different for everyone, and maybe different than it used to for you. Yes, your overall focus should be around getting back to racing and being prepared for it, and for some people that may be maintaining the same rigorous training plan that you always do. But that may not be true for everyone. And, if you are guilting yourself for not doing enough, it’s not going to help your motivation.

Since we don’t have an exact target date for your next race, it’s ok that racing is not the focal point of your training plan right now. It’s ok to take some time away from structured, metric based workouts and instead find ways to be active that bring you joy. That will help you be more motivated to train seriously when the time comes and to serve your general mental and physical health in a better way. Make sure you give value to whatever workout you do, versus telling yourself you haven’t done enough. Release yourself of the pressure to prove something to anyone other than yourself each day.

Second, you still have a Team! Unfortunately, you just don’t get to see them every day. For me, I didn’t need to see my teammates every day to be motivated by them. The main reason for that was the trust that we all had in each other. Success on a rowing team is reliant upon deep trust between all members of the crew. We all must trust that everyone is going as hard as they can always. This trust is forged through countless hours of practice on land and in the water. It comes from suffering side by side. While we can’t do that right now, we DO have all the past experiences that built that trust between our teammates and ourselves. Now is the time to lean on that. When you can’t be with your teammates every day, you must trust they are continuing the work as they are trusting you to do the same. When I had workouts to do on my own, and I wasn’t really motivated, I just would remember that I had a responsibility to my teammates to do the work, whether we were side by side or not!

Motivation is a thread woven through having races in the future and having teammates to train with. Both races and teams have something in common – they are external drivers. They are things beyond you that help to motivate you. We all also have internal drivers as motivators. Psychologists used to think that people were one or the other, but the reality is we all rely on both external and internal drivers for motivation. Right now, two major external drivers have been removed as motivators. Now is the time to explore and depend on your internal driver to keep you motivated. This is the time to pause to remember the other reasons that you love to row, especially the very personal reasons that keep you coming back. Rowing is too hard to ONLY pursue because of external reasons. My sculling coach used to say that in order to row everybody has to have a spark inside them. His job was to throw some gasoline on that spark to motivate us further, but we all had to have that internal spark. Now is the time to find out what that spark inside you is, and let that internal driver be your source of motivation to continue to train in whatever capacity that works for you.

Connected to why you row is your definition of yourself as an athlete/rower. Whether you think about it or not, we are all doing many things everyday that contribute to our definition of ourselves as a rower. While you aren’t racing or with your team, two things that may be central to your definition of yourself as an athlete, focus on doing things everyday to reinforce your definition of yourself as an athlete. While I would hope this includes some training of some kind, this isn’t JUST training: it’s getting the sleep an athlete needs; focusing on the nutrition you need as an athlete; drinking enough water. You get the idea. Find a way to call yourself an athlete every day so you stay in touch with that version of yourself even as we don’t practice as a team.

There is an opportunity here. I know that not everyone can find opportunity in times like these and I certainly can understand that. It’s a hard time. But, with a pause on racing, this is a time we can re-set. We can choose to re-define our goals and objectives, to be a different athlete, to commit to something new. In addition, we can also just choose to be a stronger version of the athlete and teammate we already are, re-affirming the goals and objectives we have set, with just a slightly different timeline. Either way, take advantage of this pause to check in with your goals, and revise or reaffirm.

I hope I have given you some ideas to connect with why you row beyond your team and racing, and hopefully some motivation as well. I’m always happy to chat with any rower about goals, why they row and motivation.

Coach Liza

One of the most common frustrations I have heard during this crisis from athletes of all ages, both from SRA and beyond is: “I don’t have the motivation to train without races and without my team. What do I do?” I want to highlight three words in this statement – motivation, races and team and discuss them further.

The first thing I want to address- there are races in your future! I know you don’t know exactly when, but you will race again. When that race day arrives, will be you be ready for it? And what does ready look like? Probably a little different for everyone, and maybe different than it used to for you. Yes, your overall focus should be around getting back to racing and being prepared for it, and for some people that may be maintaining the same rigorous training plan that you always do. But that may not be true for everyone. And, if you are guilting yourself for not doing enough, it’s not going to help your motivation.

Since we don’t have an exact target date for your next race, it’s ok that racing is not the focal point of your training plan right now. It’s ok to take some time away from structured, metric based workouts and instead find ways to be active that bring you joy. That will help you be more motivated to train seriously when the time comes and to serve your general mental and physical health in a better way. Make sure you give value to whatever workout you do, versus telling yourself you haven’t done enough. Release yourself of the pressure to prove something to anyone other than yourself each day.

Second, you still have a Team! Unfortunately, you just don’t get to see them every day. For me, I didn’t need to see my teammates every day to be motivated by them. The main reason for that was the trust that we all had in each other. Success on a rowing team is reliant upon deep trust between all members of the crew. We all must trust that everyone is going as hard as they can always. This trust is forged through countless hours of practice on land and in the water. It comes from suffering side by side. While we can’t do that right now, we DO have all the past experiences that built that trust between our teammates and ourselves. Now is the time to lean on that. When you can’t be with your teammates every day, you must trust they are continuing the work as they are trusting you to do the same. When I had workouts to do on my own, and I wasn’t really motivated, I just would remember that I had a responsibility to my teammates to do the work, whether we were side by side or not!

Motivation is a thread woven through having races in the future and having teammates to train with. Both races and teams have something in common – they are external drivers. They are things beyond you that help to motivate you. We all also have internal drivers as motivators. Psychologists used to think that people were one or the other, but the reality is we all rely on both external and internal drivers for motivation. Right now, two major external drivers have been removed as motivators. Now is the time to explore and depend on your internal driver to keep you motivated. This is the time to pause to remember the other reasons that you love to row, especially the very personal reasons that keep you coming back. Rowing is too hard to ONLY pursue because of external reasons. My sculling coach used to say that in order to row everybody has to have a spark inside them. His job was to throw some gasoline on that spark to motivate us further, but we all had to have that internal spark. Now is the time to find out what that spark inside you is, and let that internal driver be your source of motivation to continue to train in whatever capacity that works for you.

Connected to why you row is your definition of yourself as an athlete/rower. Whether you think about it or not, we are all doing many things everyday that contribute to our definition of ourselves as a rower. While you aren’t racing or with your team, two things that may be central to your definition of yourself as an athlete, focus on doing things everyday to reinforce your definition of yourself as an athlete. While I would hope this includes some training of some kind, this isn’t JUST training: it’s getting the sleep an athlete needs; focusing on the nutrition you need as an athlete; drinking enough water. You get the idea. Find a way to call yourself an athlete every day so you stay in touch with that version of yourself even as we don’t practice as a team.

There is an opportunity here. I know that not everyone can find opportunity in times like these and I certainly can understand that. It’s a hard time. But, with a pause on racing, this is a time we can re-set. We can choose to re-define our goals and objectives, to be a different athlete, to commit to something new. In addition, we can also just choose to be a stronger version of the athlete and teammate we already are, re-affirming the goals and objectives we have set, with just a slightly different timeline. Either way, take advantage of this pause to check in with your goals, and revise or reaffirm.

I hope I have given you some ideas to connect with why you row beyond your team and racing, and hopefully some motivation as well. I’m always happy to chat with any rower about goals, why they row and motivation.

Coach Liza

Coach Matt: On Erg Tests

The quote “Don’t promise when you are happy, don’t reply when you are angry, and don’t decide when you are sad.” -Ziad K. Abdelnour is often thrown around to imply that intelligent and logical people often make unwise decisions based on emotion. I’ll add “Don’t grocery shop when you’re hungry and don’t make a race plan in the middle of a race” because no, of course I don’t need the ice cream and the donuts, and no, of course backing off to “save for the sprint” isn’t going to get me to my goal.

Why should you have a race plan? What does having a race plan mean? And most commonly, what is the best race plan? Often I’ve gotten these questions just before or even during the warmup on 2k day. It’s a desperate rower’s hail-Mary, the hope that “there must be a key, some secret that if I can learn and execute will unlock the mystical erg test.” By then it’s too late to teach - too late to equip the rowers to answer those questions, so at that point I’ll give an example race plan, and if they’re lucky, they’ll have a relatively recent score to use as a starting point and we can craft a serviceable plan on the fly. But here in writing, when we have the luxuries of ample time and of logical thought, when we’re several stages removed from the heightened, anxious state that exists pre-erg test, here we can go into how and why to build an effective race plan. If there were such thing as a best race plan, then this wouldn’t be much of an article. Alas (or perhaps thankfully?) rowers will encounter different circumstances that require different race plans, and rather than try to prescribe a plan for every eventuality, we’ll lay out how to build your race plan based on your circumstances.

“Why” to have a plan is summarized in the first paragraph - if you have no plan, then you’re going to fall back into emotional decision making. In the middle of an erg test or race piece, while the lizard-brain is elbowing in on your logical self with cries of “stop this madness!” is not the time to plan anything at all, let alone how hard you want to keep working for the next couple minutes.

Circumstance 1 - “I don’t really know what I should aim for” This happens to novices, athletes coming off a long injury, or rowers who have come back to the sport after years off. If this is you, then, as soon as you can, get out of circumstance 1 - figure out what to aim for! How to do this? There are lots of “predictive workouts” (6x500, dirty dozen, 4x1k, etc), but in Philosophy of Science Norbert Wiener suggests that “The best material model of a cat is… the same cat” and I tend to agree. If you’re prepping for a 5k, do a 5k, if you’re prepping for a 2k, do a 2k. In fact, do several, because that’s the best way to simultaneously find an appropriate pacing and eliminate the foreboding that can accompany the erg test. Bear in mind that doing several 2ks isn’t “training” for a 2k, rather it’s a way of finding your correct pace. If you’re in this category, don’t get bogged down with an intricately detailed race plan, because at this point you’re just turning the coarse adjustment knob to get your pace somewhat in-focus. This is also where the “fly and die” has some value. While fly and die is not a good strategy for athletes who are trying to optimize and shave off 1 more second, for those who don’t know their pacing, it helps to “find your edge” if you’ve seen it from both sides.

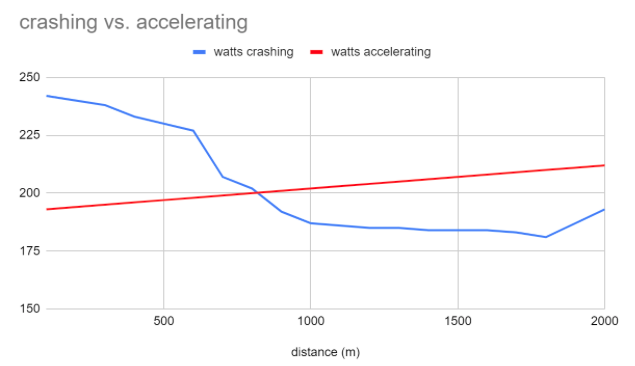

Circumstance 2 - “I have a goal, but how do I get there?” NOW, we can start building a race plan around something meaningful, and here are some questions to consider. What do you want your pacing to look like? Do you want to just hold steady for the bulk of the piece, or start 1-2 splits higher and work it down to -2/-3? Do you want to break it down by 500s/400s/300s and “castle” around your target average. Any of these are valid, but my usual prescription is to start a little slow, and accelerate throughout the piece. I like to think of it in terms of the percentage of the piece that is uncomfortable - see the charts below for a hypothetical comparison.

Why should you have a race plan? What does having a race plan mean? And most commonly, what is the best race plan? Often I’ve gotten these questions just before or even during the warmup on 2k day. It’s a desperate rower’s hail-Mary, the hope that “there must be a key, some secret that if I can learn and execute will unlock the mystical erg test.” By then it’s too late to teach - too late to equip the rowers to answer those questions, so at that point I’ll give an example race plan, and if they’re lucky, they’ll have a relatively recent score to use as a starting point and we can craft a serviceable plan on the fly. But here in writing, when we have the luxuries of ample time and of logical thought, when we’re several stages removed from the heightened, anxious state that exists pre-erg test, here we can go into how and why to build an effective race plan. If there were such thing as a best race plan, then this wouldn’t be much of an article. Alas (or perhaps thankfully?) rowers will encounter different circumstances that require different race plans, and rather than try to prescribe a plan for every eventuality, we’ll lay out how to build your race plan based on your circumstances.

“Why” to have a plan is summarized in the first paragraph - if you have no plan, then you’re going to fall back into emotional decision making. In the middle of an erg test or race piece, while the lizard-brain is elbowing in on your logical self with cries of “stop this madness!” is not the time to plan anything at all, let alone how hard you want to keep working for the next couple minutes.

Circumstance 1 - “I don’t really know what I should aim for” This happens to novices, athletes coming off a long injury, or rowers who have come back to the sport after years off. If this is you, then, as soon as you can, get out of circumstance 1 - figure out what to aim for! How to do this? There are lots of “predictive workouts” (6x500, dirty dozen, 4x1k, etc), but in Philosophy of Science Norbert Wiener suggests that “The best material model of a cat is… the same cat” and I tend to agree. If you’re prepping for a 5k, do a 5k, if you’re prepping for a 2k, do a 2k. In fact, do several, because that’s the best way to simultaneously find an appropriate pacing and eliminate the foreboding that can accompany the erg test. Bear in mind that doing several 2ks isn’t “training” for a 2k, rather it’s a way of finding your correct pace. If you’re in this category, don’t get bogged down with an intricately detailed race plan, because at this point you’re just turning the coarse adjustment knob to get your pace somewhat in-focus. This is also where the “fly and die” has some value. While fly and die is not a good strategy for athletes who are trying to optimize and shave off 1 more second, for those who don’t know their pacing, it helps to “find your edge” if you’ve seen it from both sides.

Circumstance 2 - “I have a goal, but how do I get there?” NOW, we can start building a race plan around something meaningful, and here are some questions to consider. What do you want your pacing to look like? Do you want to just hold steady for the bulk of the piece, or start 1-2 splits higher and work it down to -2/-3? Do you want to break it down by 500s/400s/300s and “castle” around your target average. Any of these are valid, but my usual prescription is to start a little slow, and accelerate throughout the piece. I like to think of it in terms of the percentage of the piece that is uncomfortable - see the charts below for a hypothetical comparison.

The red line is a rower who paced to accelerate throughout the piece and the blue line is a rower who came out too fast (by about 7 splits) and then crashed. Both rowers wind up with the same time, but the blue rower is miserable starting at about 600, while the red rower probably gets uncomfortable around 800, but isn’t truly miserable until about 1200! What a savings! The red and blue examples are hypothetical, but are meant to trace more or less what a well paced, and poorly paced 2k could look like.

In general, the more you know about where you’re aiming, the more precise and tighter your pacing should be, for example: you’ve only done one 2k this season and it was 2 months ago? You could aim for +3/+0/-3/-(6+) over each 500, but if you’ve done several and you’ve got a pretty tight grouping, maybe you go for +1/+0/-1/-2. These are just examples, and I want to emphasize that the details of the plan aren’t as important as committing yourself to it- whatever it is.

The Sprint - over the last ~15% or so you want to start committing a little harder, pushing deeper into the hole, so that by the last 20ish strokes, you’re going flat out. Use all the tools at your disposal here - pressure, rate, tech (efficiency). If your last 10 flat out strokes are just a couple splits below your average, or even if you crash in the last 5 and the split starts to climb, then you paced pretty well, but if your last 10 are wildly faster than your average, then you know you underestimated your capabilities, and you’ll want to try again and pace a little faster to home in on your hypothetical potential.

Takeaway: build your race plan well in advance, Design it logically based off of previous (ideally recent) scores. If you don’t know where to aim, there’s nothing like the real thing to give you an idea.

In general, the more you know about where you’re aiming, the more precise and tighter your pacing should be, for example: you’ve only done one 2k this season and it was 2 months ago? You could aim for +3/+0/-3/-(6+) over each 500, but if you’ve done several and you’ve got a pretty tight grouping, maybe you go for +1/+0/-1/-2. These are just examples, and I want to emphasize that the details of the plan aren’t as important as committing yourself to it- whatever it is.

The Sprint - over the last ~15% or so you want to start committing a little harder, pushing deeper into the hole, so that by the last 20ish strokes, you’re going flat out. Use all the tools at your disposal here - pressure, rate, tech (efficiency). If your last 10 flat out strokes are just a couple splits below your average, or even if you crash in the last 5 and the split starts to climb, then you paced pretty well, but if your last 10 are wildly faster than your average, then you know you underestimated your capabilities, and you’ll want to try again and pace a little faster to home in on your hypothetical potential.

Takeaway: build your race plan well in advance, Design it logically based off of previous (ideally recent) scores. If you don’t know where to aim, there’s nothing like the real thing to give you an idea.

The Importance of Recovery: Coach Ethan

Consider: What is training?

Your first thought is probably that training is the act of working out, probably repeatedly. Maybe it’s taking a 30 minute break from your job to do a core circuit, or maybe it’s going on a 16 mile run on Saturdays. Maybe it’s rowing for 2 hours three times a week, or maybe it’s rowing for 12 sessions a week as you try to make the national team.

What is a training plan?

Chances are, it makes you think of some sort of cycle or calendar, with workouts of varying intensity and duration spread throughout. And depending on how serious or experienced of an athlete you are, the more workouts you’ll have and the harder they’ll be. Seemingly, a training plan is just a list of workouts arranged throughout the week (or month, or day, or year).

Alas, this conception of training and training plans is incomplete. A fuller picture of training needs to consider a number of factors, including nutrition, hydration, injury prevention, and--crucially--recovery, which we’ll focus on here.

So let’s be clear: A hard workout will never make you faster on its own. Working out doesn’t improve your performance; recovery after a workout does. Adaptation to a physiological stressor occurs while you are in recovery. Quite literally: you become a faster rower during the periods of time when you are NOT working hard! If you want to engage in a well-rounded, effective training program, the recovery period is equally as important as the exercise stimulus.

Your first thought is probably that training is the act of working out, probably repeatedly. Maybe it’s taking a 30 minute break from your job to do a core circuit, or maybe it’s going on a 16 mile run on Saturdays. Maybe it’s rowing for 2 hours three times a week, or maybe it’s rowing for 12 sessions a week as you try to make the national team.

What is a training plan?

Chances are, it makes you think of some sort of cycle or calendar, with workouts of varying intensity and duration spread throughout. And depending on how serious or experienced of an athlete you are, the more workouts you’ll have and the harder they’ll be. Seemingly, a training plan is just a list of workouts arranged throughout the week (or month, or day, or year).

Alas, this conception of training and training plans is incomplete. A fuller picture of training needs to consider a number of factors, including nutrition, hydration, injury prevention, and--crucially--recovery, which we’ll focus on here.

So let’s be clear: A hard workout will never make you faster on its own. Working out doesn’t improve your performance; recovery after a workout does. Adaptation to a physiological stressor occurs while you are in recovery. Quite literally: you become a faster rower during the periods of time when you are NOT working hard! If you want to engage in a well-rounded, effective training program, the recovery period is equally as important as the exercise stimulus.

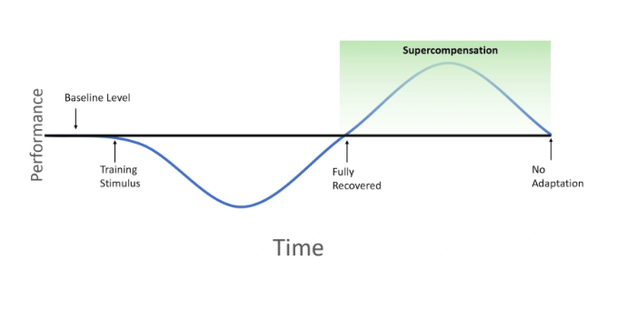

Let’s walk through the graph above:

1. Baseline Level

This is pretty obvious. It’s basically how fast of a rower you are right now, prior to a workout.

2. Training Stimulus

This is the workout itself. You stress your body in some way. Maybe it’s crazy hard sprint pieces; maybe it’s a long, light steady state piece. You tax the various energy systems in your body and the immediate effect is to actually get slower.

3. Recovery Period

This is where the magic happens. This is when your performance sinks below your baseline level for an extended period of time; the entire time when the curve dips below the horizontal line in the graph. If you do 12x500m on the erg, and 12 hours later I ask you to pull a 2k--you probably won’t PR, because your body will not have fully recovered.

During this time, your body undergoes a number of physiological adaptations as it replenishes your energy stores, repairs muscle and tissue tears from the workout, and improvements at the cellular level (i.e. increasing the density of mitochondria). Fundamentally, this is the period during which your body is actually adapting and improving. If you don’t let yourself properly recover from a workout, you’ll never get faster.

4. Supercompensation

At a certain point, your performance level continues to creep up and up, until you’ve surpassed the initial baseline level. Congratulations--your body is now in supercompensation! You’re officially a faster rower than you were before the last workout. This is the best time for you to apply another training stimulus and repeat the process all over again.

Performance Over Time

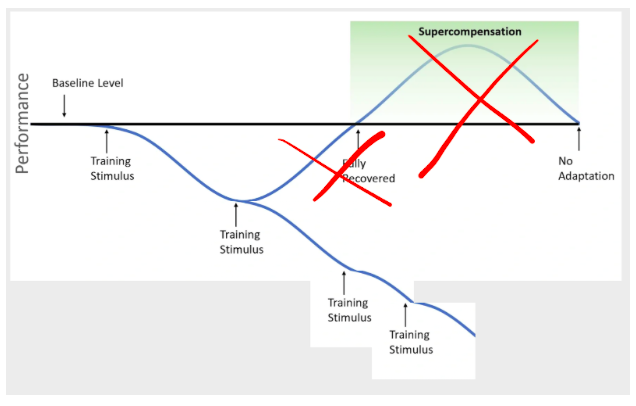

If you don’t allow for proper recovery, your performance over time could look something like this (exaggerated) graph. Your performance level continues to sink, and in spite of numerous hard workouts, you are only getting slower! Bummer.

1. Baseline Level

This is pretty obvious. It’s basically how fast of a rower you are right now, prior to a workout.

2. Training Stimulus

This is the workout itself. You stress your body in some way. Maybe it’s crazy hard sprint pieces; maybe it’s a long, light steady state piece. You tax the various energy systems in your body and the immediate effect is to actually get slower.

3. Recovery Period

This is where the magic happens. This is when your performance sinks below your baseline level for an extended period of time; the entire time when the curve dips below the horizontal line in the graph. If you do 12x500m on the erg, and 12 hours later I ask you to pull a 2k--you probably won’t PR, because your body will not have fully recovered.

During this time, your body undergoes a number of physiological adaptations as it replenishes your energy stores, repairs muscle and tissue tears from the workout, and improvements at the cellular level (i.e. increasing the density of mitochondria). Fundamentally, this is the period during which your body is actually adapting and improving. If you don’t let yourself properly recover from a workout, you’ll never get faster.

4. Supercompensation

At a certain point, your performance level continues to creep up and up, until you’ve surpassed the initial baseline level. Congratulations--your body is now in supercompensation! You’re officially a faster rower than you were before the last workout. This is the best time for you to apply another training stimulus and repeat the process all over again.

Performance Over Time

If you don’t allow for proper recovery, your performance over time could look something like this (exaggerated) graph. Your performance level continues to sink, and in spite of numerous hard workouts, you are only getting slower! Bummer.

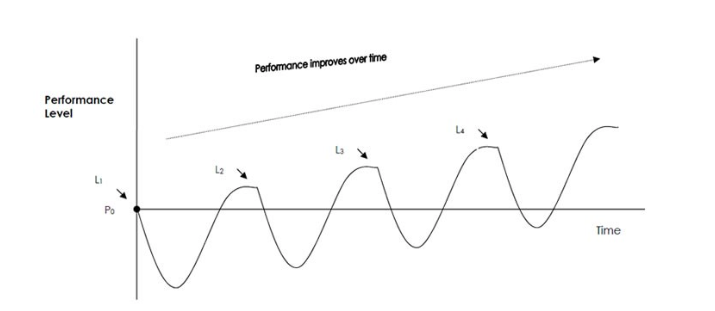

With a properly executed training program, you can recover properly between workouts. Then, when your body is in the supercompensation period, your current performance level is higher than the baseline level. If you apply a training stimulus now, you will undergo another recovery period and come out the other side even faster!

Keeping Track of Recovery

How do you use this information to be a better rower? Well, it’s important to keep track of your recovery process with a training journal. This will help you notice patterns in your recovery that can inform important decisions in your training. For instance, you may notice that anytime you do a good hard Anaerobic Threshold workout, the next day’s session is always subpar, no matter what it is. This is an indication that your body might need two days to recover properly, and the day after AT would be a good chance for a light session, or no session at all.

It’s also a good idea to keep track of stressors outside of rowing, since those can play an important role in recovery. Record how much sleep you get. Make a note of how much you have going on at work or school. Consider repeated, stressful social situations. A busy week at work might be a good opportunity to have a lighter week of training, since your body might be less able to recover quickly.

But without a training journal where you can keep track of your workouts and the factors that impact your recovery, you won’t be able to notice these patterns.

Keeping a Recovery Journal

In addition to keeping track of your workouts, try adding in some extra information. Here are a few basic questions to get you started. If you rank each question 1-10, then you can formulate a “recovery score” for yourself. You don’t have to answer these questions every single day--just once a week will be enough to start noticing patterns. This is also not an exhaustive list of stressors that can impact your recovery, but try it out and see if it helps give you a more complete picture of your training.

How many hours of quality sleep do you get each night?

How well have you been hydrating every day?

How well have you been fueling with proper nutrition?

Do you have adequate downtime during the week to relax?

How much emotional stress have you experienced this week?

How busy are you with work/family/school?

Conclusion

While it’s easy to get caught up in the workouts, a complete training program has to consider recovery as an essential component to improving over time. Adding more and more, harder and harder workouts will not necessarily improve your performance. Physiological, psychological, and technical adaptation actually occurs during the recovery period after the stress of a workout, so without adequate recovery, additional sessions won’t yield additional speed. Fundamentally, recovery is as important to training as the workout itself.

How do you use this information to be a better rower? Well, it’s important to keep track of your recovery process with a training journal. This will help you notice patterns in your recovery that can inform important decisions in your training. For instance, you may notice that anytime you do a good hard Anaerobic Threshold workout, the next day’s session is always subpar, no matter what it is. This is an indication that your body might need two days to recover properly, and the day after AT would be a good chance for a light session, or no session at all.

It’s also a good idea to keep track of stressors outside of rowing, since those can play an important role in recovery. Record how much sleep you get. Make a note of how much you have going on at work or school. Consider repeated, stressful social situations. A busy week at work might be a good opportunity to have a lighter week of training, since your body might be less able to recover quickly.

But without a training journal where you can keep track of your workouts and the factors that impact your recovery, you won’t be able to notice these patterns.

Keeping a Recovery Journal

In addition to keeping track of your workouts, try adding in some extra information. Here are a few basic questions to get you started. If you rank each question 1-10, then you can formulate a “recovery score” for yourself. You don’t have to answer these questions every single day--just once a week will be enough to start noticing patterns. This is also not an exhaustive list of stressors that can impact your recovery, but try it out and see if it helps give you a more complete picture of your training.

How many hours of quality sleep do you get each night?

How well have you been hydrating every day?

How well have you been fueling with proper nutrition?

Do you have adequate downtime during the week to relax?

How much emotional stress have you experienced this week?

How busy are you with work/family/school?

Conclusion

While it’s easy to get caught up in the workouts, a complete training program has to consider recovery as an essential component to improving over time. Adding more and more, harder and harder workouts will not necessarily improve your performance. Physiological, psychological, and technical adaptation actually occurs during the recovery period after the stress of a workout, so without adequate recovery, additional sessions won’t yield additional speed. Fundamentally, recovery is as important to training as the workout itself.

Matt's Warm-Up Wisdom

How many times have you heard your coach proclaim on an erg test day, “Do a race warmup, we’ll begin in xx minutes.” What do you do? If you find you’re spending the first half of the allotted time wondering exactly that, then here are some tips you can use to arm yourself for the next time it happens!

Race warm up should be built around 3 basic steps:

1. The specifics of each segment will vary person to person, and you should pay attention to your body and what seems to work for YOU. You might need 20 minutes of light steady state to get your joints ready to work hard, or you might be fine with only 5 minutes light before moving on to the higher intensity of the rate builders. On the water at races, this often involves a drill to help everybody clear their heads and get the crew swinging together.

2. Getting ready for higher rates should look something like 1' on/ 1' off or 20 strokes on/ 20 strokes off, or 30 str/30 str, 20 str/30 str, 30"/45" etc. These should be at race pressure, and you should build starting at steady-state rate up to your race rate (for example, starting at 20 spm and building up 2 or 3 beats each interval through 32 spm.) Do a couple bursts at your race rate (depending on your interval format). The goal is to be breathing hard by the end; get your heart rate up above your aerobic zone to cue your metabolism that it's time to fight-or-flight. Again, you should be breathing hard after a race warm up, you should be sweating, you should be just a little worried that you went too hard on the warm up and started dipping into your "race reserves" - that’s a perfectly normal worry, and 10-to-1 you didn’t! You should not be gasping or falling off the erg unable to stand.

3. Getting a quick rest to recover before the race is important, since if you're adequately warmed up for a 2k, it means you worked hard. It means you primed your aerobic and anaerobic systems, burned through some glycogen stores, and that stuff needs some time to restock. Generally this is between 5-10 minutes of resting and active recovery. Again, the correct proportions will vary person to person (except on the water, when this part looks like rowing to the staging area and waiting to get called up, and you’re more or less at the mercy of the race officials and if it’s running on time). Do some dynamic stretching here, some more light recovery-paced steady state, or walking (this is your chance for a last-minute haircut!).

Once you get your 2k warm up dialed in, start thinking about how it applies to your pre-race warm up at regattas. Start with your event time, and work backwards through the three steps. Remember, that at a regatta, your warm up is the same for the whole crew, so if you know you're an "I need 30 whole minutes of steady state before I can start applying the rate/press" person, then you know that you need to start doing that 20-30 minutes before your hands-on is scheduled (go for a run, lunges, jumping jacks, etc.)

Whew that was a lot about just warming up! Takeaway is: include the 3 basic steps, don't be afraid to experiment on your own, listen to your body!

Race warm up should be built around 3 basic steps:

- 1) get your body moving - Steady state for ~10 minutes

- 2) get yourself ready for race pace - row in bursts of race pressure building the rates up to your race pace

- 3) leave enough time to "recover" before you start - ~5-10 minutes between finishing your bursts and starting the race

1. The specifics of each segment will vary person to person, and you should pay attention to your body and what seems to work for YOU. You might need 20 minutes of light steady state to get your joints ready to work hard, or you might be fine with only 5 minutes light before moving on to the higher intensity of the rate builders. On the water at races, this often involves a drill to help everybody clear their heads and get the crew swinging together.

2. Getting ready for higher rates should look something like 1' on/ 1' off or 20 strokes on/ 20 strokes off, or 30 str/30 str, 20 str/30 str, 30"/45" etc. These should be at race pressure, and you should build starting at steady-state rate up to your race rate (for example, starting at 20 spm and building up 2 or 3 beats each interval through 32 spm.) Do a couple bursts at your race rate (depending on your interval format). The goal is to be breathing hard by the end; get your heart rate up above your aerobic zone to cue your metabolism that it's time to fight-or-flight. Again, you should be breathing hard after a race warm up, you should be sweating, you should be just a little worried that you went too hard on the warm up and started dipping into your "race reserves" - that’s a perfectly normal worry, and 10-to-1 you didn’t! You should not be gasping or falling off the erg unable to stand.

3. Getting a quick rest to recover before the race is important, since if you're adequately warmed up for a 2k, it means you worked hard. It means you primed your aerobic and anaerobic systems, burned through some glycogen stores, and that stuff needs some time to restock. Generally this is between 5-10 minutes of resting and active recovery. Again, the correct proportions will vary person to person (except on the water, when this part looks like rowing to the staging area and waiting to get called up, and you’re more or less at the mercy of the race officials and if it’s running on time). Do some dynamic stretching here, some more light recovery-paced steady state, or walking (this is your chance for a last-minute haircut!).

Once you get your 2k warm up dialed in, start thinking about how it applies to your pre-race warm up at regattas. Start with your event time, and work backwards through the three steps. Remember, that at a regatta, your warm up is the same for the whole crew, so if you know you're an "I need 30 whole minutes of steady state before I can start applying the rate/press" person, then you know that you need to start doing that 20-30 minutes before your hands-on is scheduled (go for a run, lunges, jumping jacks, etc.)

Whew that was a lot about just warming up! Takeaway is: include the 3 basic steps, don't be afraid to experiment on your own, listen to your body!